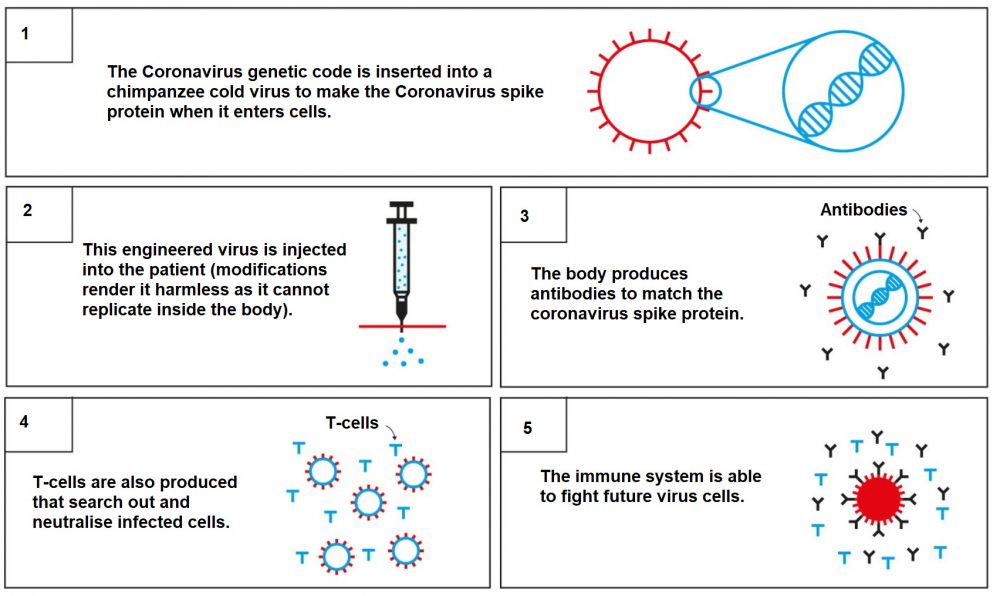

The vaccine – called ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 – uses a harmless, weakened version of a common virus that causes colds in chimpanzees

Is it effective against the new variants?

Data on the highly contagious Covid-19 variant identified in England do not suggest that the AstraZeneca / Oxford vaccines will be less effective against it.

“We have the most data on the UK variant. That doesn’t suggest that it will be any less well protected against by the vaccine,” said Wei Shen Lim, chair of Covid-19 Immunisation on Britain’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation, on Jan 13.

The Oxford University researchers who developed the jab say it has a similar efficacy against the variant compared to the original Covid-19 strain it was tested against.

Professor Andrew Pollard, a chief investigator on the Oxford vaccine trial, said new data suggests “the vaccine not only protects against the original pandemic virus, but also protects against the novel variant, B.1.1.7”.

But research has revealed that the Oxford vaccine “provides minimal protection” against mild disease caused by the variant of Covid-19 first discovered in South Africa, according to early data from a small trial.

A study suggested the Oxford vaccine was only 10 per cent effective against the variant.

The study, from South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand and Oxford University, analysed the E484K mutation in some 2,000 people, most of whom were young and healthy.

The team found that the vaccine had “substantially reduced” efficacy against the South African variant compared to the original strain of Sars-Cov-2.

South African authorities suspended the country’s vaccination programme on Monday 8 Feb following this discovery, stating more research is needed.

Professor Salim Abdool Karim, leader of South Africa’s Covid response, said: “We don’t want to end up with a situation where we vaccinate a million people or two million people with a vaccine that may not be effective at preventing hospitalisation and severe disease.”

However, scientists advising the World Health Organization warned against jumping to conclusions and awarded emergency-use licenses to two versions of the Oxford-AstraZeneca jab on Monday 15 February.

Many experts have pointed out that the study on the South African variant was small. While it looked into whether the vaccine prevents mild and moderate disease in a group of mostly young people, it did not look at whether the vaccine prevents severe disease, hospitalisation and deaths.

Sarah Gilbert, professor of vaccinology at the University of Oxford, told the BBC she was confident the vaccine would prevent severe illness.

However, a tweaked Oxford vaccine which can cope with the new coronavirus variants circulating in Britain will be trialled in the coming months before being rolled out in the the autumn, scientists have said. And the World Health Organization looks set to approve the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine for use in developing countries.

Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech both said their vaccines were effective against new variants of the coronavirus discovered in Britain and South Africa, but they are slightly less protective against the variant in South Africa, which may be more adept at dodging antibodies in the bloodstream.

As a precaution, Moderna has begun developing a new form of its vaccine that could be used as a booster shot against the variant in South Africa.

It was also announced on Feb 5 that the UK Government has struck a deal with the German drugs firm CureVac for 50million doses of vaccine designed to beat future variants.

Does it differ to Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines?

Yes. The jabs from Pfizer and Moderna are messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines.

Conventional vaccines are produced using weakened forms of the virus, but mRNAs use only the virus’s genetic code.

An mRNA vaccine is injected into the body where it enters cells and tells them to create antigens.

These antigens are recognised by the immune system and prepare it to fight coronavirus.

No virus is needed to create an mRNA vaccine. This means the rate at which the vaccine can be produced is accelerated.

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines have both been approved in the US.

The UK Government began the roll-out of the Pfizer vaccine on Dec 8.

Unlike the Pfizer vaccine, the Oxford jab does not require ultra-low temperatures.

The Oxford jab requires temperatures between 2C and 8C and can be stored for at least six months.

This is the typical temperature of a domestic refrigerator and this will make deployment of the vaccine much easier and faster.