Vaccination stalled in Africa

While India battles a catastrophic second wave of Covid-19 infections, health officials in Africa are watching with alarm as their immunisation campaigns, heavily dependent on vaccine imports from the subcontinent, stutter to a halt.

“Two months ago, India was doing a victory dance and handing out vaccines around the world like candies,” said Dr Ayoade Alakija, co-chair of the Africa Vaccine Delivery Alliance, which is co-ordinating distribution on the continent. “They were saying how wonderfully they had done because of the immunity and the youth of their population. Look where India is today.” The crisis in India, where as many as 3,000 people are dying a day, has provided proof, Alakija and others argued, of what could happen in Africa if vaccination campaigns are not rapidly accelerated and the virus is allowed to spread and mutate. Africa and other under-vaccinated parts of the world urgently need to catch up, said Professor Trudie Lang, head of the Global Health Network at the University of Oxford. “India is a horrifying warning about the dangers of complacency,” she said. African health officials aim to vaccinate at least 30 per cent of the 1.2bn population by the end of the year, rising to 60 per cent or higher after that. But supply constraints, logistical problems and vaccine hesitancy mean immunisation campaigns have been patchy.

Shot shortage

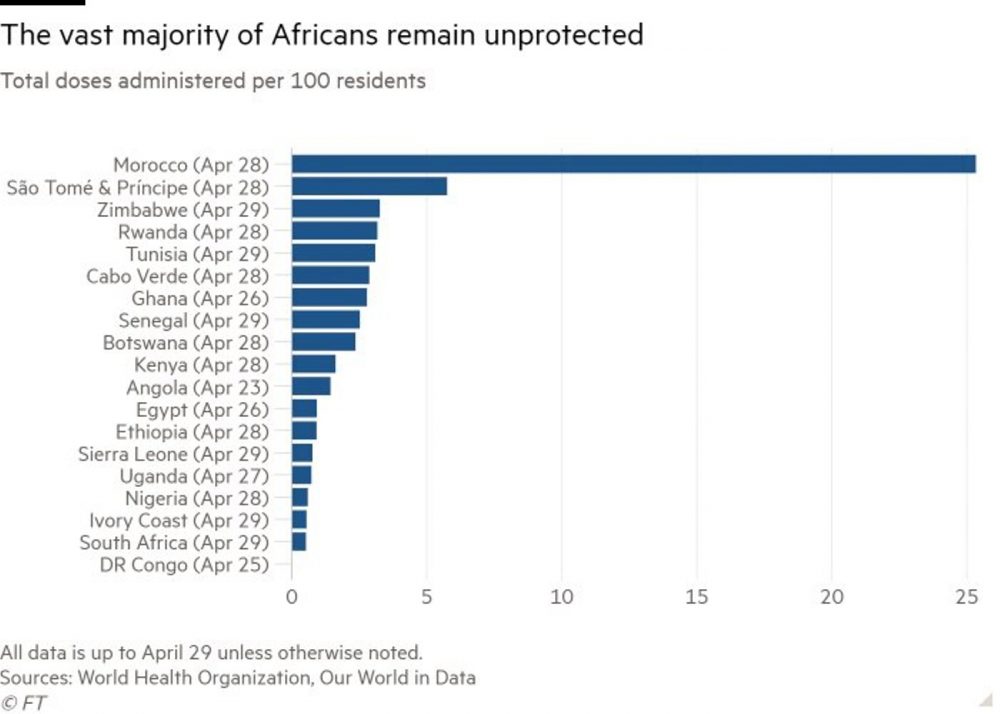

In total, Africa has received just 32m doses of vaccine, of which about 18m have made it into people’s arms. Doses of the Oxford/AstraZeneca shot from the multilateral Covax programme make up the bulk of jabs deployed so far, but supply has dried up after Delhi blocked exports by the Serum Institute of India to battle its own outbreak. “There are no vaccines,” said Alakija. “It’s difficult to say there’s a problem with rollout when you don’t have anything to roll out,” she said, adding that no new supplies are expected from Covax until June.

Those countries that have distributed their limited supplies efficiently, including Rwanda, Senegal, Ghana and Botswana, have already used up their Covax doses, which only began arriving last month. Even so, Rwanda and Ghana, among the best African performers, have managed to administer fewer than three doses per 100 inhabitants. (The UK has given 71 doses per 100 people).

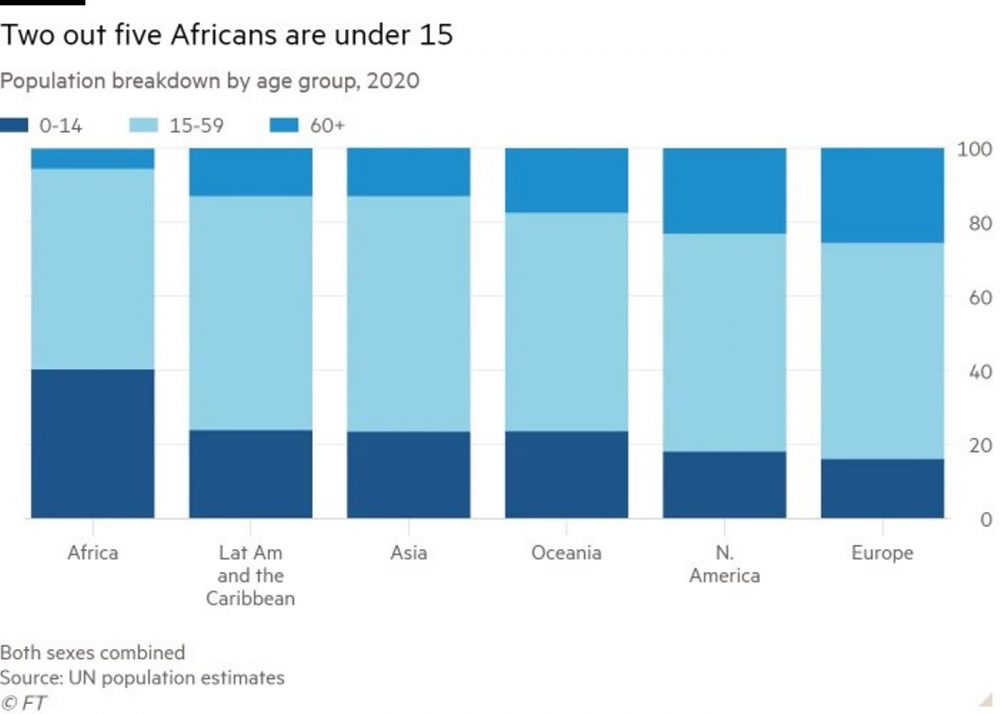

The continent’s youthful population, with a median age of 19, and comparatively low death toll to date has led some to argue that Africa may not need to vaccinate as large a proportion of the population to control the pandemic as some other parts of the world. Officially only about 120,000 people have died of Covid in Africa, less than 4 per cent of the global total, though that may significantly underestimate the true number.

Kate O’Brien, director of immunisation, vaccines and biologicals at the World Health Organization, said western countries’ drive to get as close to complete vaccine coverage as possible — and potentially penalise less-covered countries through vaccine-passport schemes — may be putting undue pressure on poorer countries to follow suit. “We don’t necessarily need to have the same goal across all countries,” she said, adding that countries have to juggle a range of budgetary and health priorities, including combating other diseases such as malaria, HIV and tuberculosis.

But officials leading the African response remain committed to vaccinating at least 60 per cent of the population. “If we are to defeat this pandemic — which we have to do for our own survival and the survival of our economies — we have to do this at speed and at scale,” said Dr John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinating children Given the young median age in many African countries, the 60 per cent immunisation target would probably involve vaccinating some children, according to Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO’s regional director for Africa. Chart showing Africa’s population breakdown by age group

“The logical way is to target the areas that have been hit most severely, like the cities,” said Moeti. “Even if younger people don’t get seriously ill, they can transmit the virus.” In Israel, some children aged 12 to 16 with underlying conditions that make them more vulnerable to Covid have already been given the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine. In the US, it is increasingly likely 12- to 15-year-olds will be vaccinated before the next school year begins in September.

But for some scientists it remains a contentious proposal, given that the disease poses little risk to children and that the vaccines are yet to be approved for those under 18. “From the point of view of public health ethics, you would only be vaccinating [children] to try to suppress the infection, not really for any benefit to the under-18s,” said Robert Dingwall, professor of sociology at Nottingham Trent University and a member of the UK government’s vaccine advisory committee. “Most ethicists would describe that as inexcusable.” Maarten Postma, professor in pharmacoeconomics at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, said there was “a clear ethical issue” about giving vaccines that may cause deadly side effects, however rare, to people who are unlikely to be severely affected by Covid. This particularly applied, he said, to the use of the AstraZeneca shot in Africa, given the elevated risk — however small — of blood clots. The AstraZeneca question The deployment of the AstraZeneca vaccine has been complicated further by evidence from one study that the jab did not prevent mild and moderate infections associated with the variant first identified in South Africa, which has since spread around the continent. Even though it is the worst-affected country in Africa, South Africa has halted the rollout of the AstraZeneca vaccine. The Democratic Republic of Congo, where vaccine hesitancy is high, is returning 1.2m doses of the shot to Covax after deciding not to use it.

kengasong at Africa CDC disagreed strongly with decisions not to use certain shots. “You don’t go to war with what you need, you go to war with what you have,” he said. African governments, he said, were reliant on the Covax scheme and therefore have almost no choice over which vaccines they deploy. “We have to go with AstraZeneca,” he said, adding that people who take the contraceptive pill — let alone those who contract Covid — run a far greater risk of blood clots. “Let me just say this very clearly. The benefit outweighs the risk.” Data from Europe suggest that about one in 100,000 people who receive the AstraZeneca vaccine report the rare blood-clotting event, which is lethal about a fifth of the time.

One big fear is that, if the vaccination rollout fails in Africa, virus mutations could emerge that are more dangerous to the African population than current strains. “Will the new variants be as forgiving to Africa as the first wave of variants has been?” asked OB Sisay, senior Covid adviser at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. Sisay said he was worried that confusing regulatory decisions in Europe about use of the AstraZeneca vaccine as well as a perception that Covid was not as deadly for Africans had already damaged vaccine confidence. “If people don’t see that they are sick or dying from Covid, then they don’t take it seriously to get vaccinated,” Sisay said, speaking from Gambia. But before African governments can even begin to address hesitancy, they need sufficient, guaranteed supplies to mount the required full-scale campaigns and push for compliance, said Alakija at the Vaccine Delivery Alliance. “Right now Covax has ground to a shuddering halt,” she said. “We’re at the point where we’re rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.”