AHO outraged by kidney trafficking business in Egypt

Through interviews and documents obtained by Al Jazeera, the investigation exposes officials who have been giving out false papers for personal gain to facilitate organ trafficking.

The organ-trafficking ring preyed on poor Yemenis willing to travel to Egypt and sell a kidney in a desperate bid to gain income that would keep them going, at least for a while.

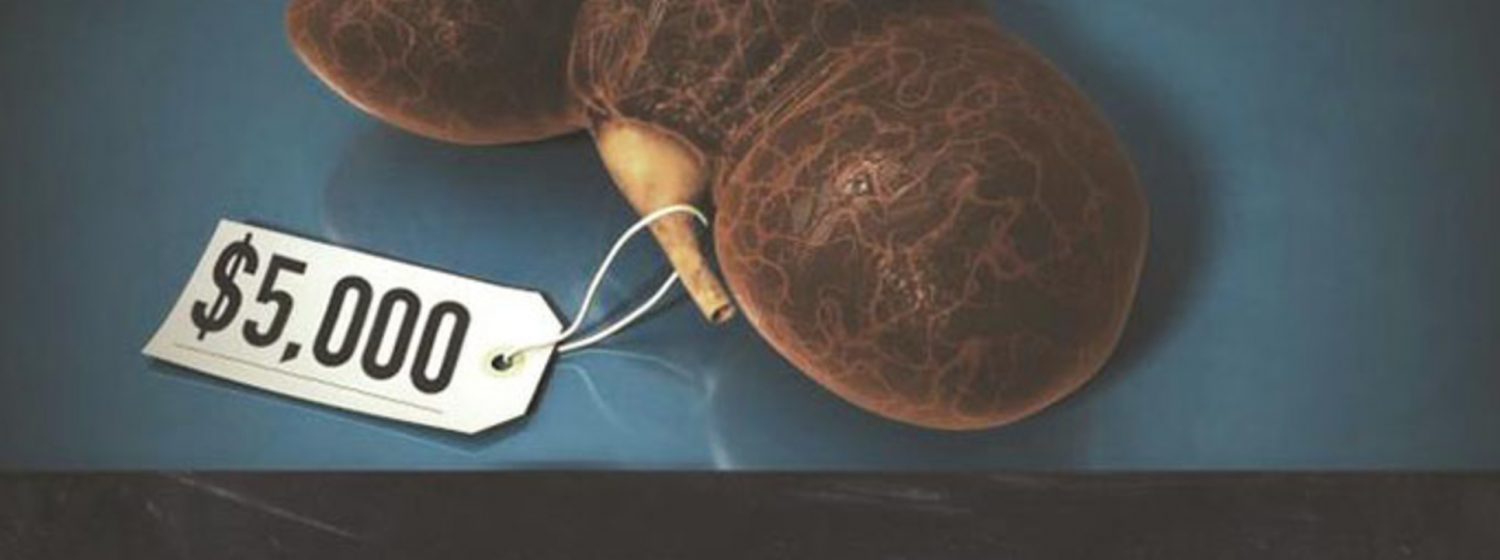

One of these Yemenis was Ahmed*, who was told in 2014 by a friend that he could get $5 000 for one of his kidneys. He agreed, and before he knew it, he was on a plane to Cairo.

Ahmed* sold his kidney for $5 000 in Egypt in 2014 [Al Jazeera]

At the time, Yemen was not yet home to the world’s worst humanitarian crisis and the destructive war that has left 80 percent of its population in need of humanitarian assistance.

But it was already the poorest country in the Middle East with half the population living below the poverty line.

In Yemen, selling your organs is not illegal. However, it is illegal in Egypt, where three donors Al Jazeera spoke to, and hundreds of others who told their story to a Yemeni NGO, went to sell their organs.

Recruited by a broker

The trafficking ring found its donors through brokers in Yemen who would find willing individuals and connect them with brokers in Egypt to arrange their travel, accommodation, and surgeries.

The brokers get involved for different reasons. One Egyptian broker Al Jazeera spoke to became involved after his brother needed a kidney and bought one from a Yemeni donor.

“After the operation, [the Yemeni donor] went back home and we stayed in touch … he started telling me he could find others willing to donate if I knew of anyone who needed transplants.”

The Yemeni broker Al Jazeera spoke to was initially recruited to be a donor but was not compatible with any of the ring’s clients.

The Yemeni broker began recruiting others to donate when he found out he was incompatible with the ring’s clients [Al Jazeera]

Instead, he was asked to find others in Yemen who would be willing to sell a kidney and was told he would make a $1,000 commission on every donor he recruited.

Nabil al-Fadhil, head of the Yemeni Organization for Combating Human Trafficking, told Al Jazeera that his organisation verified some 1,000 cases of organ sales, but they were certain that there were tens of thousands.

Nabil al-Fadhil, head of the Yemeni Organization for Combating Human Trafficking [Al Jazeera]

“Of the thousand we interviewed, 900 had sold their kidneys – then came back to Yemen as brokers looking to find new victims,” al-Fadhil said in an interview at the end of 2018.

Egyptian hospitals implicated

Patients in need of a kidney would get in touch with the network, which maintained a pool of candidates to act as donors.

Once a compatible donor was found, the surgery would be performed almost immediately and the donor would be flown back to Yemen with little to no time to recover, increasing the chances of health complications and making it difficult for a donor to return to any sort of labour-intensive work.

Several hospitals across Egypt have been accused of operating on these donors, and the government has busted prominent doctors and institutions working in trafficking rings over the past five years.

“We work with public and private hospitals,” the Egyptian broker confirmed to Al Jazeera.

In al-Fadhil’s records from 2014, one hospital kept coming up, one that saw no arrests in spite of his notifying anti-trafficking organisations in Egypt: Wadi El Neel Hospital in Cairo.

It is one of 48 hospitals licensed by the Egyptian government to perform transplant procedures and Al Jazeera sources in Egypt say it is referred to as the Mukhabarat (or Intelligence) Hospital by many Egyptians.

“The Mukhabarat Hospital is used for Yemeni [donors] only, and the receiving patients are Saudis and other foreigners,” the Yemeni broker told Al Jazeera.

Al Jazeera reached out to the hospital and spoke to an individual who presented himself as a manager there.

He denied the accusations, citing Egyptian law: “If the patient is Yemeni then the donor must be Yemeni, with a passport accredited by the embassy, and the embassy’s approval to donate. This law has been in place for years. Everything but that is nonsense.” In Egyptian hospitals licensed to perform transplant surgeries, donors are also required to testify that they are donating by choice, either in writing or on camera, which all three of our Yemeni donors did.

‘Yemeni embassy’s involvement’

All three donors claim they sold their organs to non-Yemeni nationals.

“They found a woman from the UAE who needed a kidney, so we did the blood and tissue tests, and found that we were a match. So, I went in for the surgery … Afterwards, she asked me how much I got, I said $5,000. She told me that she had paid $50,000,” Ahmed* told us.

Besides having to be of the same nationality, the donor and recipient of an organ must be related, according to the Yemeni embassy in Cairo.

Brokers claim that the Yemeni Embassy in Cairo facilitated the organ trafficking trade by processing false papers [Al Jazeera]

Proof of relation is signed off on by the Yemeni Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Justice, but it is the responsibility of the embassy that receives the paperwork and coordinates with the Egyptian Ministry of Health to finalise approval for a transplant

According to the Yemeni broker Al Jazeera spoke to, they were quite accommodating – for a price.

“The embassy announced it was illegal to donate an organ unless it was to a family relation and the relationship would have to be approved by the embassy.

“There were 15 or 20 people waiting [to donate] but they stopped them. So, the network sent me to Yemen to get the necessary paperwork to prove a relationship.” the broker told Al Jazeera.

“I made a deal with a judge to pay him 80,000 Yemeni rials ($320) per case, and he’d get it signed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I had done three when they got in touch and told me to stop because they’d found someone at the embassy who could approve the requests for $500 each,” he explained. According to the Egyptian broker, cooperation by Yemeni officials was instrumental to the process. “To be honest, our work would be impossible without cooperation with government entities there (in Yemen) that makes bringing Yemenis over to Egypt much easier for us.”

Al-Fadhil said he had come to suspect the embassy’s involvement.

“There were laws in Egypt being broken, and our embassy could have acted, but they just denied it … the embassy is still involved to this day because this business makes them a lot of money,” he said.

After repeated efforts to contact the embassy, Al Jazeera received a response from the media attache, Baleegh al-Mukhlafi, who said: “The only thing the embassy does is to address medical authorities after the documents required by the [Egyptian] Ministry of Health and the courts have been completed.”

The embassy denied any other form of involvement.

Yemenis trapped in Egypt

There are now many Yemenis already in Egypt who are resorting to selling their organs to make ends meet, says al-Fadhil.

They came to Egypt to escape the violence in Yemen and are unable to return because of the worsening situation and because of the closure of Sanaa airport.

There was a decrease in overall cases in 2014 and 2015 when the Egyptian government began denying entry to Yemeni citizens, but there are still many Yemeni refugees trapped in Egypt.

“Yemenis who went to Egypt when the war broke out are now stuck there and have been forced to sell their kidneys out of desperation. We’ve recorded more than 200 such cases,” al-Fadhil told Al Jazeera.

What al-Fadhil and others working to end this trade would like to see is a change in government policies that would end this trade. However, given the state Yemen is in today, it is unlikely that any significant changes will be made. Anti-trafficking organisations, like most other NGOs, are struggling to continue operations in the war-torn country.

“We still face threats and a lot of pressure. This is probably going to be my last interview because we’re living in a country where even humanitarian work is prohibited.”

A few months after our interview in 2018, al-Fadhil’s organisation was shut down by Houthi forces and he was forced to leave Yemen.

“There’s no way we can actually work to stop this when we’re in the middle of war and destruction and poverty and people can barely afford food.

“There’s no solution except to stop the war, rebuild the country, hire people … that’s the only solution . . . and it’s just not possible.” — AL JAZEERA NEWS.